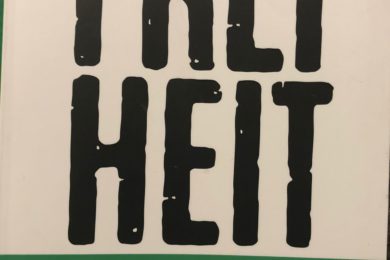

English below

Автор: Ольга Самборська

Берлін, 2 січня 2023 року

Сиджу в берлінському метро і чекаю на свого потяга. За мною на металево-гратовій лавці сидить похилого віку жіночка і щось бурмоче. Я спочатку не звертала на неї уваги, аж поки її голос не ставав все гучнішим і пробивав мою свідомість. Між бурмотіння чула слова: Заксенгаузен, Потсдам, Голланд, бомбардування. Коли я почула останнє слово, стала прислухатися більше, бо бомбардування чітко асоціюється в мене зараз лише з Україною. Але до чого тут бомбардування і стара бабця на лавці? Чи її хвилює Україна? Далі я почала вловлювати зміст її марення, бо говорила вона виключно сама з собою.

Таких багато по Берліні. Безхатченки або просто хворі, які з’їхали з глузду або вірніше їх збила з глузду травма, нанесена суспільством, в якому людина приречена природою знаходитись і травмуватись.

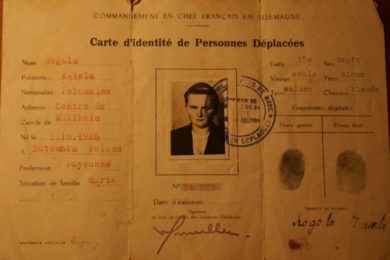

Розповідь старої жінки в помаранчевому кашкеті, який провалювався в зачухане пальто, в масці від ковіду була малозрозумілою. Зі всього я зрозуміла наступне: вона дитиною пережила страхіття бомбардування Німеччини під час Другої світової війни. Її мати, щоб врятуватися від війни дітей, втікла до Нідерландів, де їх рятувала одна жінка. Виглядає так, що вони втратили будинок в Потсдамі, а Заксенгаузен потрапив хтось з їх родини, можливо батько. Жіночка кружляла цією розповіддю взад-вперед, повторювала слова і навіть цілі речення. Я застигла в розгубленості. Мене пробудив до тями прибулий жовтий потяг. І хоча треба було підійматися і йти, я не могла зрушити з місця. Нашвидкуруч записала її останні репліки на диктофон і миттєво вскочила до свого потягу, залишивши на пероні частку постісторії Другої світової війни. А до Німеччини вже втікають інші від своєї війни.

Зрозуміло, що травма війни не закінчується з її закінченням, але живе в її жертвах ще довго, а може і вмирає з ними. Ще старі травми війни минулого століття не повмирали, а вже бухтять інші війни та продукують нові травми. «Якими будуть наші діти через 40-60 років, коли травми стануть особливо активними?» – запитую себе я. Дослідженнями встановлення, що дитячі травми активуються зі зміною гормонального стану дорослого організму, особливо в час криз середнього віку. Важко передбачити всі наслідки травмування в дитинстві. Відомо лише одне, що з травмами потрібно працювати вже зараз. Їх варто проговорювати з рідними, близькими, психологами. Травма – це не саме проживання шоку і лиха. Травма – це те, що залишається від нього в пам’яті, якщо по-людськи її не опрацювати, не говорити з нею і не поважати її.

Саме тому я як українка і як вчитель початкових класів для українських дітей-біженців в Берліні не могла не звернути увагу на травмовану війною німкеню в німецькому метро. З 24 лютого 2022 року я з травмою на «ти». Вона знає мене, а я її, в лице. Ми бачимо одна одну на відстані.

Ми познайомились, коли я вперше почула про початок війни в моїй дорогій серцю Україні, в що я ніколи не вірила попри всі попередження в міжнародних медіях. Я пам‘ятаю лише, як тоді травма сіла поруч на моє ще тепле після сну ліжко і поклала свою важку долоню на моє серце, защемила його холодом і вже більше не відпустила. Моє серце після цього ніби застигло в грудях. Встати на ноги я вже не змогла.

Перед монітором ноутбука на колінах я провела цілий день. Потім цілу ніч. Потім ще один день, і ще одну ніч. Я втратила відчуття межі між днем і ніччю. Росіяни «полюбляли» бомбити українські міста саме вночі. Нечиста сила. Вони бомбили їх безжально в Україні, а від вибухів я здригалася в Берліні. І так я не спала цілий тиждень, а потім другий. Коли чуда не сталося і війна не припинилася, в що я так свято вірила і просила Бога про це, травма хамовито по-путінськи посміхнулася мені і закрила за собою дверцята моєї душі. Вона дала зрозуміти, що поселилася там надовго.

Я просила місцевих психологів, які мали б бути навчені комунікації з травмами різного ґатунку, допомогти мені прогнати цього звіра (ТРАВМУ) з моєї душі, хоча і розуміла, що зі зникненням московського звіра і його щупалець над світовою душею, нічого не буде і травми не позбутися.

Світ для мене став дуальним, подвійно-фальшивим. На одній його частині як на стародавній римській арені були українці-гладіатори, на яких було випущено здичавілого бика з рогами у формі літери «Z“. Трагічну виставу в міжнародному медійному амфітеатрі спостерігав весь світ, махаючи жовто-блакитними прапорцями як підтримку. Мої психологи теж були з публіки цього театру. Вони штучно-мажорно намагалися використати в розмові зі мною завчені на своїх психологічних студіях методи для заспокоєння, але жоден з них не зміг відкрити двері всередині моєї душі і вигнати звідти травму. Вона, ця пані, була незвичайною, модерною, віртуальною. Вона використала мою чутливість , якої в моїх українській тотожності аж занадто, і змогла візуалізувати все, що відбувалося на моїй батьківщині в стінах берлінської квартири, або конкретніше розбурхати мою мигдалину до неабияких коливань. Та і розбурхувати останню особливо не треба було, бо вона і так вже була розхитана передчуттям великої біди. Десь за пів року до війни я почала відчувати неабияку тривогу у своєму тілі. Я колись жартувала, що маю псячу душу, яка передчуває лихо, символізуючи його завиванням його напрямку. Так в дитинстві моя мама пояснювала виття сільських псів на вулиці. І ми дуже боялися, щоб наш пес не завивав на лихо. Коли вночі вили сусідькі пси, то всі прислухалися чиї саме пси завивають і біля якого двору вони виють, бо там вони попереджають про біду у господаря. А коли одного разу завив наш пес, ми похололи. Невдовзі помер наш батько. А після похорону пес перестав вити. Попереджав, співчував, плакав? Так і моя душа перестала тривожитись, як почалася війна. Вона ніби заспокоїлась: «Сталося!» Але коли сталося, то серце не витримало того, що сталося.

Як дитина миру, я ніколи не могла уявити війну, бо знала про неї лише з телевізора, військових парадів ветеранів і бряжчання їх металевих орденів на уніформах. Нас виховували так, що війна вже ніколи не може повторитись, бо за мир було заплачено занадто високу ціну – 20 мільйонів жертв у Другій світовій війні. І це була помилка. Нас, українців ніколи не готували до війни. Колись в радянській школі, коли двері «залізної брами» починали рипіти особливо голосно, а міжнародні дипломати й президенти намагалися їх змастити якимись політичними мастилами, ми мали підготовку з громадянської оборони, вчилися стріляти в шкільному тирі, слухали про заходи безпеки, тренувалися слухати сирени. Коли двері “залізної брами” вже не рипіли, всьому давався відбій і у війну ніхто не вірив. Мир для післявоєнного покоління був даністю як повітря, сонце і дощ. Але післявоєнне покоління може на раз стати й довоєнним. Війна вже давно стала поміткою історії, яка ділить її на періоди: повоєнні й довоєнні, в яких людство спершу живе, а потім у війні себе знищує. А тих, хто залишився, заморожує в травмі.

Я скористалася ще кількома сесіями психологічної допомоги, але чим далі, тим більше розуміла, що психолог чи психотерапевт, який не бачить чи не проживає зі своєю країною лихо, не може тобі допомогти. Психологи виливали на мене купу різної інформації, від якої мене нудило, аніж допомагало. Мені бракувало співчуття в їх голосі, людського тепла і розуміння, тобто того, чого боїться травма. Штучність психолога її лише лоскоче, розпалюючи її на жахливій регіт панічних атак та інших страхітливих станів.

Коли я зрозуміла свою безпорадність в ситуації, в якій опинилася як і мільйони українців, а нас понад 40 мільйонів в Україні, і понад 10 мільйонів в діаспорі, я вирішила повернутися обличчям до тих, в кого живе емпатія – до своїх земляків, але не за допомогою, а з рішення дарувати емпатію таким самим як і я, а то і самим найменших серед нас – дітям.

Так я стала вчителем початкового класу для дітей-українців в Берліні. Мені дали завдання навчити їх німецької мови для переходу в німецьку школу, але я дала собі завдання навчити їх емпатії один до одного і самих до себе.

З першого дня в школі я починаю урок, стаючи перед дітьми з відкритими обіймами. Діти вже знають, що це означає ніщо інше, як те, що вони всі разом можуть підбігти до мене так само з розпростертими обіймами. Це наш перший ритуал, який ми вивчили, назвавши його «обіймочки». Так само ми розлучаємося після уроків. Я теж навчила дітей вітати один одного обіймами. Помітила, що після цього діти не такі агресивні і люб‘язніші один до одного.

Під час уроків, особливо коли ми багато пишемо, ми робимо розминання рук, масуємо пальчики, обличчя і тіло. На закінчення цих вправ, я обов‘язково попрошу дітей погладити себе своїми ж руками та пожартувати при цьому: «Ой, який я у мене гарний. Як я себе люблю.» На останньому реченні я прошу дітей обняти самих себе своїми дитячими обіймами, погладити себе і в такий спосіб відчути власну опіку самих над собою. Діти пізнають себе як окремі особистості. І дуже регочуться, коли це роблять. Бачу, що це роблять з задоволенням. І так має бути. Самоемпатія – це теж емпатія.

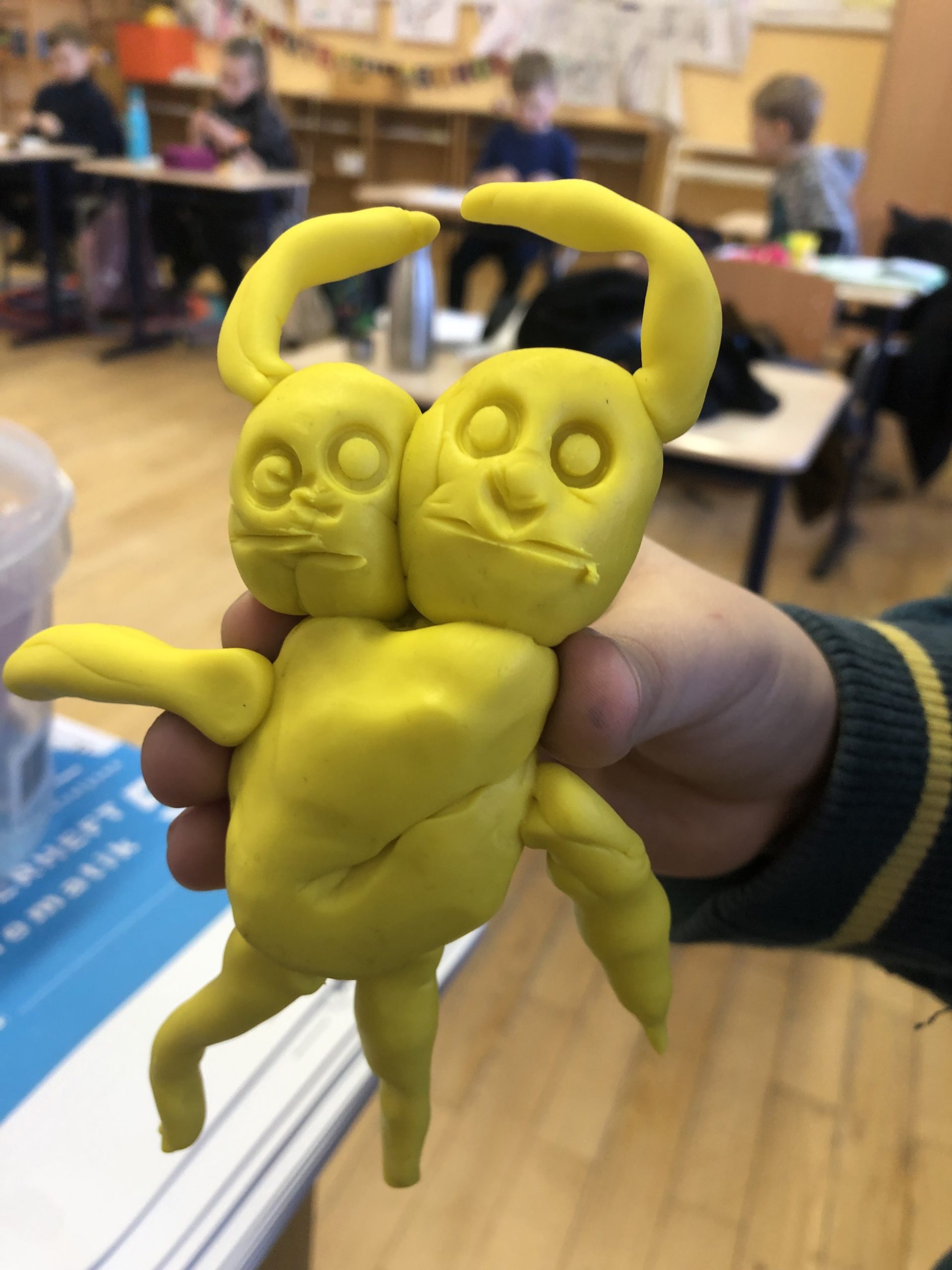

Коли діти ще не знали, що таке емпатія, я пояснила їм це як здатність розуміти іншого і себе. При цьому я прикладала звичайне дзеркала на рівні мозку і пояснювала дітям, як мозок бачить іншого, тобо як функціонують наші дзеркальні гормони. А коли ми займаємося ручною працею як-то ліпимо щось з пластиліну я прошу їх зліпити самих себе так, як вони себе уявляють. Це може бути фігура тіла або якийсь предмет, яким вони себе уявляють. Коли я бачу, що робота вже підходить до завершення, я починаю вести з ними наступну розмову:

А коли ми займаємося ручною працею як-то ліпимо щось з пластиліну я прошу їх зліпити самих себе так, як вони себе уявляють. Це може бути фігура тіла або якийсь предмет, яким вони себе уявляють. Коли я бачу, що робота вже підходить до завершення, я починаю вести з ними наступну розмову:

«Скажіть мені, чи було таке, що ви почувалися колись зле, не дуже добре, у вас не було настрою, вас насварили батьки, вас образили інші діти, з якими ви гралися? І вам було так недобре всередині?»

«О, так!!!!» – гучно і з великою жалістю до себе відповідають діти, кожен зі своїм забарвленням жалю в голосі.

«Ну тоді я вам подарую один лайвхак, що можна зробити в цьому випадку, хочете?»

«Так!»-захоплено відповідають.

«Так от, ви берете оцю пластилинову фігурку, тобто себе, або вашу улюблену іграшку, з якою ви спите, скажімо і уявляєте, що це і є ви самі. Тоді гладите себе по головці або обнімаєте, так як це робить з вами мама або тато, або бабуся, або дідусь або будь-хто, хто вас любить. Пошкодуйте себе, бо хто, як не ви перші знаєте, що вас потрібно пошкодувати?»

Діти посміхаються і маленькими пальчиками погладжуть пластилінові фігурки власного зображення. Поки так.

Коли діти призвичаюються шкодувати себе в такий спосіб, іду трохи далі до наших йога-подорожей, які ми часто практикуємо для застосування методу Ріка Гансона ХЕАЛ, згадуючи приємні речі з України й перебуваючи в цьому позитивному досвіді аж поки він не заповнить їхню клітинну пам’ять доверху. Цього разу я попрошу їх сісти на нашого йога-човна (поза йоги, коли дитина сидить і руками-веслами гребе уявну воду) і доплисти в уяві до тих сцен, коли над їх головами летіли бомби, а вуха фіксували розриви ракет і снарядів. Я попрошу їх пригадати їх самих в ті хвилини, коли їм було страшно і травма кістлявими долонями стулила їхні сердечка. Я не буду їх запитувати про деталі, але попрошу обняти їх в тому стані, в якому вони себе пам‘ятають. Так само обняти, як вони обнімають своїх плюшевих ведмедиків, песиків чи ляльку. А потім посадити уявно переляканого себе у свій йога-човен і привезти до Берліна, де все тихо і спокійно. Я знаю, що травма не витримає цих обіймів. Занадто крижані її руки, щоб витримати тепло дитячої самоемпатії.

На завершення нашої подорожі читаю їм історію про маленького равлика, яку діти дуже люблять. В ній йдеться про те, що маленький равлик одного разу, повзаючи на галявині, дуже злякався песика, який гуляв там. З переляку равлик заповз у свою равликову хатинку і більше звідти не вилазив. Кожного дня до нього підходили різні комахи, які запрошували його погратися разом. Вони пояснювали йому, що песик вже давно за межами галявини, але страх скував равлика по самі його мацаки. Равлику постійно уявлявся пес і він не хотів залишати свою мушлю-хатинку, де він почувався в безпеці, хоча й самотньо. Так тривало довший час, аж поки вітру не стало шкода малого равлика. Він придумав полоскотати равликового носика пір‘їнкою. Коли той чхнув, то так чхнув, що аж катапультувався зі своєї мушлі. Опинився на галявині, побачив сонечко і так зрадів, що подумав що потрапив у рай, так йому зробилося добре. І всі його друзі-комахи раділи йому. І він врешті сам переконався в тому, що песика не має на галявині й можна вільно гратися там. А вночі йому приснився сон, в якому песик говорить йому, що вони, пси, взагалі равликів не їдять. Діти на прикладі цієї психотерапевтичної історії розуміють деструктивну дію страху. Пригадують свої історії, коли їм було по-справжньому страшно, але вони не мали своєї мушлі-схованки. Так влаштована людська природа, що у випадку страху, ми ховаємося самі в себе. Хтось має витягнути нас звідти.

Першими, хто це має зробити, батьки. Вони мають розуміти, що їх стрес війни передається дітям, навіть якщо вони про це не говорять. Дітей не можна ні в якому разі залишати надовго наодинці, нікуди віддавали, навіть якщо йдеться про власний обов‘язок з захисту країни. Бодай один з батьків має залишитися з дитиною! Діти не можуть тікати, не можуть взяти в руки зброю. Єдине, що їм залишається, це деперсоналізація як захисний механізм психіки від божевілля. Щоб цього не сталося, дітям потрібне постійне відчуття безпеки в особі батьків або близьких людей. Непроговорена травма заговорить через десятки років, як от зараз вона говорила старою німкенею на пероні берлінського метро. Їй вже навряд чи можна допомогти, але вона допомагає собі сама, проговорюючи те, що з нею коїлося 60 років тому. У травми немає відліку часу, бо вона живе своїм життям, осіла на дні підсвідомості.

На жаль, люди влаштовані так, що керуються платою пам’яті все життя і навіть передають її з покоління в покоління, якщо її не чистити від сміття, не виносити його на поверхню, на світло. Все темне боїться світла. А ще більше, коли це світло або тепло огортає її обіймами емпатії до людини або емпатії людини до самої себе. Якщо цього не робити, то психіка застосує спосіб божевілля як захисний механізм, щоб травмований почав говорити сам з собою, шкодувати себе. Ми вже не будемо розуміти його, але його розумітиме травма. І це важливо.

Тому виношу цю історію сюди, у віртуальний простір, щоб нагадати про те, що травми як паразити підсаджуються в людину, коли вона, або її душа в найбільш вразливому стані. Вони заселяють порожній простір в людині, коли його надає душа, яка в цей час ховається “в п’яти”. Але психотравму можна звідти виперти, якщо знову наповнитись любов‘ю, співчуттям до себе і до інших. Це допоможе повернути душу на її місце, звільнившись від страху, який своєю чергою боїться любові й турботи ближніх.

Підозрюю, що у випадку травмованої німкені-дитини з берлінського метро цього не сталося. Але що сталося, то сталося. У кожного свій шлях. Колись і вона звільниться від травми-паразита, якщо не в цьому житті, то в майбутність мандрівках її душі. А світ колись звільниться від війн, які продукують травми. А кожен з нас може звільнити того, хто поруч, від травми, просто тепло обіймаючи його.

English:

Author: Olha Samborska

Berlin, 2.01. 2023

I am sitting in the Berlin subway waiting for my train. Behind me, an elderly woman sits on a metal and lattice bench and mutters something. I didn’t pay attention to her until her voice became louder and louder and pierced my consciousness. Between the mutterings, I heard words: Sachsenhausen, Potsdam, Holland, bombing. When I heard the last word, I began to listen more, because I now clearly associate the bombing only with Ukraine. But what does the bombing have to do with the old lady on the bench? Does she care about Ukraine? Then I began to catch the meaning of her delirium because she was talking exclusively to herself.

There are many such people in Berlin. Homeless people or just sick people who have gone crazy, or rather, they have been driven crazy by the trauma inflicted by a society in which people are doomed by nature to be and be injured.

The story of an old woman in an orange cap who fell into a furry coat and wore a covid mask was unclear. I understood the following: as a child, she experienced the horrors of the bombing of Germany during World War II. Her mother fled to the Netherlands to save her children from the war, where they were rescued by a woman. It seems that they had lost their house in Potsdam, and someone from their family, possibly their father, had been imprisoned in Sachsenhausen. The woman spun this story back and forth, repeating words and even whole sentences. I was frozen in confusion. I was awakened by the arrival of a yellow subway train. Although I had to get up and go, I couldn’t move. I hastily recorded her last remarks on a dictaphone and instantly jumped on my train, leaving a piece of post-World War II history on the platform. Others are already fleeing their war to Germany.

It is clear that the trauma of war does not end with its end, but lives on in its victims for a long time, and perhaps dies with them. The old traumas of the last century’s wars have not yet died, and other wars are already raging and producing new traumas. “What will our children be like in 40-60 years, when the traumas will become especially active?” – I ask myself. Studies have shown that childhood traumas are activated by changes in the hormonal state of the adult body, especially during midlife crises. It is difficult to predict all the consequences of childhood trauma. All we know is that traumas need to be dealt with now. They should be discussed with family, friends, and psychologists. Trauma is not the mere experience of shock and disaster. Trauma is something that remains in the memory if you don’t process it in a human way, talk to it, and respect it.

That is why, as a Ukrainian and as a primary school teacher for Ukrainian refugee children in Berlin, I could not help but notice a German woman traumatized by war in the German subway. “Since February 24, 2022, I have been on a first-name basis with trauma. She knows me and I know her by sight. We see each other from a distance.

We met when I first heard about the outbreak of war in my dear Ukraine, which I never believed despite all the warnings in the international media. All I remember is how trauma sat next to me on my bed, still warm from sleep, and put its heavy palm on my heart, pinched it with cold and never let go. My heart felt as if it had frozen in my chest. I could not get to my feet.

I spent the whole day in front of the laptop monitor on my knees checking if my whole family and friends over there were alive. Then the whole night was the same. Then another day, and another night. I lost the sense of the boundary between day and night. The Russians “liked” to bomb Ukrainian cities at night. It was an evil power. They were bombing them mercilessly in Ukraine, and I was shuddering from the explosions in Berlin. And so I did not sleep for a whole week, and then the second. When the miracle didn’t happen and the war didn’t stop, which I believed in so strongly and asked God to stop the craziness, the trauma smiled at me in a rude Putin-like way and closed the door of my soul behind me. It made it clear that it had settled there for a long time.

I asked local psychologists, who were supposed to be trained in dealing with traumas of all kinds, to help me drive this beast (TRAUMA) out of my soul, even though I understood that with the disappearance of the Moscow beast and its tentacles over the world’s soul, nothing would happen and I would not be able to get rid of the trauma.

The world for me became dual, double-fake. In one part of it, as in an ancient Roman arena, Ukrainian gladiators were unleashing a wild bull with horns in the shape of the letter “Z”. The whole world watched the tragic performance in the international media amphitheater, waving yellow and blue flags in support. Bloody corrida! My psychologists were also from the audience of this theater. They artificially tried to use the methods of calming me down that they had learned in their psychological studies, but none of them could open the door inside my soul and expel the trauma from there. She, this trauma lady, was unusual, modern, and virtual. She used my sensitivity, which I have in abundance in my Ukrainian identity, and was able to visualize everything that was happening in my homeland within the walls of my Berlin apartment, or more specifically, to stir my amygdala to great extent. And there was no need to stir the latter because it was already shaken by the premonition of great trouble. About six months before the war, I began to feel a lot of anxiety in my body. I used to joke that I had a dog’s soul that sensed trouble, symbolizing it by howling its direction. This is how my mother explained the howling of village dogs in the street when I was a child. And we were very afraid that our dog would not howl for trouble. When the neighboring dogs howled at night, everyone listened to whose dogs were howling and near which yard they were howling, because there they warned of trouble at the owner’s house. And when one day our dog howled, we got cold. Soon our father died. And after the funeral, the dog stopped howling. Did he warns, sympathizes, or cry? Similarly, my soul stopped worrying when the war started. It seemed to calm down: “It has happened!” But when it did, my heart could not bear what happened.

As a child of peace, born in the seventies, I could never imagine the war, because I knew about it only from TV, soviets military parades of veterans, and the clanging of their metal medals on their uniforms. We were brought up to believe that war could never happen again because the price for peace was too high – 20 million victims in World War II. And this was a mistake. We, Ukrainians, were never prepared for war. Once upon a time, in Soviet school, when the doors of the Iron Gate began to creak especially loudly, and international diplomats and presidents tried to grease them with some kind of political lubricant, we had civil defense training, learned to shoot in the school shooting range, listened to security measures, and practiced listening to sirens. When the “iron gate” doors no longer rattled, everything was put on hold and no one believed in the war. Peace for the postwar generation was a given, like air, sun, and rain. But the postwar generation can become the prewar generation overnight. War has long been a marker of history that divides it into periods: postwar and prewar, in which humanity first lives in peace and then destroys itself in war. And those who remain are frozen in trauma.

I took advantage of a few more sessions of psychological help, but the further I went, the more I realized that a psychologist or psychotherapist who does not see or live with the disaster in their country cannot help me. Psychologists poured out a lot of different information on me, which made me sicker than it helped. I lacked compassion in their voices, human warmth, and understanding, which is what trauma is afraid of. The artificiality of the psychologist only tickles it, inciting it to terrible laughter of panic attacks and other terrifying states.

When I realized my helplessness in the situation in which I found myself, like millions of Ukrainians, and there are more than 40 million of us in Ukraine and more than 10 million in the diaspora, I decided to turn my face to those who have empathy, to my fellow countrymen, but not with help, but with the decision to give empathy to people like me, and even to the smallest among us, children.

That’s how I became a primary school teacher for Ukrainian children in Berlin. I was given the task of teaching them German language to prepare to a German school, but I gave myself the task of teaching them empathy for each other and for themselves.

On the first day at school, I start the lesson by standing in front of the children with open arms. The children already know that this means nothing more than that they can all run up to me with open arms and I will hugs them alltogather. This is the first ritual that we learned, and we called it “hugs.” This is also how we part after school. I also taught the children to greet each other with hugs. I noticed that after that children are not so aggressive and are kinder to each other.

During the lessons, especially when we write a lot, we do hand warm-ups and massage our fingers, face, and body. At the end of these exercises, I make sure to ask the children to stroke themselves with their own hands and make a joke: “Oh, how beautiful I am. I love myself so much.” In the last sentence, I ask the children to embrace themselves with their childlike hugs, to stroke themselves, and in this way to feel their own care for themselves. Children recognize themselves as separate individuals. And they laugh a lot when they do this. I see that they do it with pleasure. And that’s the way it should be. Self-empathy is also empathy.

When the children did not yet know what empathy was, I explained it to them as the ability to understand the others and oneself. At the same time, I used an ordinary mirror at the level of the brain and explained to the children how the brain sees another person, or how our mirror neurons function.

And when we are doing manual labor, like making something out of clay, I ask them to mold themselves the way they imagine themselves. It can be a body figure or some object they imagine themselves to be. When I see that the work is nearing completion, I start having the following conversation with them:

“Tell me, has there ever been a time when you felt bad, not very good, you were not in a good mood, your parents scolded you, or you were hurt by other children you were playing with? And you felt so bad inside?”

“Oh, yes….” the children answer loudly and with great self-pity, each with their own color of regret in their voice.

“Well, then I’ll give you a life hack that can be done in this case, do you want to try it?”

“Yes!” they answer enthusiastically.

“So, you take this plasticine figure, that is, yourself, or your favorite toy that you sleep with, let’s say, and imagine that it is you. Then you pat yourself on the head or hug yourself, just like your mom, dad, grandma, grandpa, or anyone who loves you. Feel sorry for yourself, because who knows better than you that you need to feel sorry for yourself?”

The children smile and stroke the plasticine figures of their image with their small fingers. So far, so good.

When the children get used to feeling sorry for themselves in this way, I move on to our yoga journeys, which we often practice to apply Rick Hanson’s HEAL method, recalling pleasant things from Ukraine and staying in that positive experience until it fills their cellular memory to the brim. This time, I will ask them to sit on their yoga boat (a yoga pose where a child sits and paddles imaginary water with his or her hands) and swim in their imagination to those scenes when bombs were flying over their heads and their ears were recording the explosions of rockets and shells. I will ask them to recall themselves in those moments when they were afraid and trauma closed their hearts with bony palms. I will not ask them about the details, but I will ask them to hug them in the state in which they remember themselves. Just like they hug their teddy bears, dogs, or dolls. And then to put the imaginary frightened self in their yoga boat and bring them to Berlin, where everything is quiet and calm and save. I know that trauma cannot withstand this hug. Her hands are too icy to withstand the warmth of a child’s self-empathy.

At the end of our trip, I read them a story about a little snail that the children love. It says that one day a little snail, crawling on a lawn, got very scared of a dog that was walking there. Frightened, the snail crawled into its snail house and never came out again. Every day different insects came up to him and invited him to play together. They explained to him that the dog had long since left the meadow, but fear shackled the snail to his very tentacle. The snail constantly imagined the dog and did not want to leave his shell house, where he felt safe, although lonely. This went on for a long time until the wind felt sorry for the little snail. He decided to tickle the snail’s nose with a feather. When the snail sneezed, it sneezed so hard that it was catapulted out of its shell. He found himself in a meadow, saw the sun, and was so happy that he thought he was in paradise, he felt so good. And all his insect friends were happy for him. And he finally saw for himself that there was no dog on the lawn and he could play there freely. And at night he had a dream in which the dog told him that they, dogs, do not eat snails at all. Using this psychotherapeutic story as an example, children understand the destructive effect of fear. They recall their own stories when they were really scared, but they did not have their own shell hiding place. It is human nature that when we are afraid, we hide in ourselves. Someone has to pull us out of there.

Parents are the first to do this. They must realize that their war stress is passed on to their children, even if they do not talk about it. Children should never be left alone for long periods of time, nor should they be sent anywhere, even if it is their own duty to protect the country. At least one parent must stay with the child! Children cannot run away, and cannot take up arms. The only thing left to them is depersonalization as a defense mechanism of the psyche against madness. To prevent this from happening, children need a constant sense of security in the person of their parents or loved ones. The unspoken trauma will speak out in decades, just as it did to the old German woman on the Berlin subway platform. She can hardly be helped, but she helps herself by talking about what happened to her 60 years ago. The trauma has no time limit, because it lives its own life, settling at the bottom of the subconscious.

Unfortunately, people are designed in such a way that they are guided by the memory board all their lives and even pass it on from generation to generation if it is not cleaned of debris, if it is not brought to the surface, to the light. Everything dark is afraid of the light. And even more so when this light or warmth envelops it in the embrace of empathy for a person or a person’s empathy for himself. If this is not done, then the psyche will use the method of insanity as a defense mechanism so that the traumatized person begins to talk to himself, to feel sorry for himself. We will no longer understand him, but the trauma will understand him. And this is important.

That is why I am bringing this story here, in the virtual space, to remind us that traumas, like parasites, get into a person when he or she, or his or her soul, is in the most vulnerable state. They inhabit an empty space in a person when it is provided by the soul, which at this time is hiding “in the heels”. But psychodrama can be pushed out of there if you are filled with love and compassion for yourself and others. This will help to return the soul to its place, freeing it from fear, which in turn is afraid of the love and care of others.

I suspect that this did not happen in the case of the traumatized German woman in the Berlin subway. But what happened? Everyone has their own path. Someday she will be free of the parasite trauma, if not in this life, then in the future journeys of her soul. And the world will one day be free of wars that produce trauma. And each of us can free the person next to us from trauma by simply hugging them warmly. Or just putting your own palm over the other person’s palm as I do it with children to show them that we are all warmblooded creatures radiating just warmth. I ask my student to put their hands on the table. Then I go through the class putting my hand over their palms one after the other without touching them. Then I ask if they feel the warmness. What do you think they answer?