English version below

14.01.2023

Автор: Ольга Самборська

Берлін

Якщо практикувати Ди-По-Зу регулярно, можливо сподіватися на чисті віконечка їх душ, через які можна буде краще розглянути дитину, а може і апостола в ній. Одного з дванадцяти.

В українських класах для дітей біженців за правилами Сенату шкільництва Німеччини має бути дванадцятеро дітей як дванадцять апостолів) Коли я йшла на цю посаду, я не зовсім розуміла, чому саме дванадцять. Ну дванадцять так дванадцять. “Більше уваги кожному” – раділа про себе я. Та радість моя була короткою. Вже в перші місяці роботи в школі почали скоса дивитися на мене місцеві вчителі, в класах яких вдвічі більше дітей. Хто з них чемніший, мило мені посміхався, але прохолода відчувалася по нижніх чакрах. Але я трималася. Похитнулася, коли в школі виникла критична ситуація з персоналом і одному вчителю потрібно було залишити школу. Звісно, що в масах почалося бродіння, бо ніхто не хотів “бути зайвим”, тобто скороченим.

На майданчику школи проходила я якось повз групу вчителів. “А який в тебе контракт?” – отримала як каштаном по голові (якраз стояли під цим деревом) зненацька запитання. Я не швидко зорієнтувалася і відповіла, хоча на такі питання недоречно відповідати як і недоречно запитувати. Моя відповідь викликала гусяче гелготіння серед вчителів. Запитала в чому справа. Пояснили про скорочення і на їх думки під скорочення маю потрапити саме я “з моїми трьома учнями”. Насправді учнів маю не трійко, але дванадцятеро, але для тих у кого їх двадцять чотири або навіть двадцять вісім звісно є різниця. Вчителі шипіли-гелготіли далі, пояснюючи свою зайнятість-обтяжливість роботою. Я попросила вияснити це питання з директором і залишилася гусячу зграю.

Невдовзі відбулася розмова з директором. Ситуацію прояснили. Вчителі українських класів в німецькій школі йдуть за особливим статусом і не підлягають скороченню, яке поширюється на школу як таку. Я встряхнула крильми, розправила їх і поплила в своє вільне плавання школою. За порадою директора стала оминати гусей.

Пройшло ще кілька тижнів. Вчора, після останнього уроку тижня, я зрозуміла, чому в класах для дітей-біженців саме дванадцятеро учнів, а нет двадцять чотири як в регулярних класах. Коли дивишся на обличчя дітей-біженців, з яких одне зовсім не посміхається, інше – постійно дивиться з під-лоба, і намагаєшся витягнути з дітей душу для посмішки і марно, коли випускаєш на перерву, а після неї не можеш вгамувати згустки енергії в одну хвилю, коли під час уроку ні з того ні з сього почуєш: “А в наш будинок влучила ракета і знищила його”, коли дитина просто почула слово “будинок” як триггер. Таких “коли”-несподіванок повний урок і повний день. І поступово розумієш, що працюєш з дійсно травматизованими пандемією-війною дітьми і в такому випадку цей клас прирівнюється до класу дітей-інвалідів, яких теж має бути до дванадцяти, тобто менше звичайного класу, бо з ними важче працювати. Єдина різниця, що вчителів до класів дітей-інвалідів спеціально до такої роботи готують. Якщо дитина-інвалід навчається в звичайному класі, до неї спеціально приставлено вчителя-фахівця, який її супроводжує.

Звичайно, українські діти-біженці не є інвалідами в прямому сенсі цього слова, але індивідуальний підхід до них був би не зайвим. І не завадила б професійна підготовка вчителів для роботи з дітьми з травмами. І повага до вчителя, який, не маючи спеціальної підготовки, змушений спілкуватися з травмованими дітьми один на один, також не завадила б.

Посада вчителя класу для початківців, або так званого Willkommensclass, є новою в німецькій шкільній системі. Зазвичай на неї набирають вчителів з акцентом на кваліфікацію викладача німецької мови як іноземної для інтеграції дитини в німецьку школу. Звичайно, такі вчителі німецької мови не завжди є підготовленими травматерапевтами. Іноді для них організовують разові та годинні вебінари про те, як працювати з травмованими дітьми. Єдине, чого бракує, – це систематичної методології для вчителів, як розмовляти з травмою у дітей.

Травма, українська дитяча травма, не говорить українською мовою, як я сподівалася. Вона промовляє до мене писклявим голосом дитини, затиснутої десь між тілом і духом, коли перелякана війною душа вже була на шляху до втечі з тіла, але зачепилася за свідомість і вчепилася в неї. Вона пищить, іноді кричить, плаче, б’ється в істериці, ніби просить зняти її з невидимого гачка свідомості і витягнути назовні.

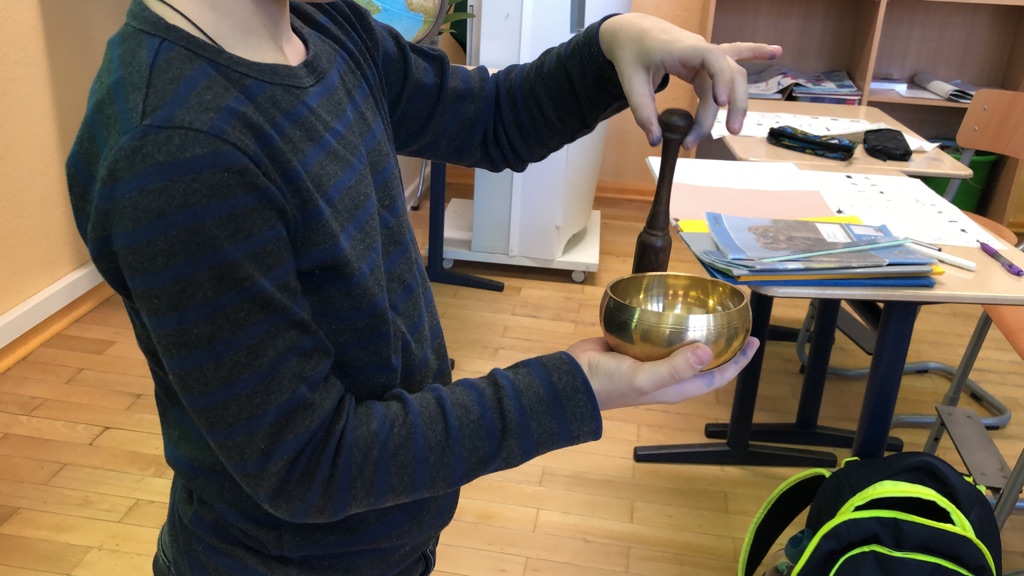

Я довго намагалася витягнути травмовану душу дитини на розмову, але вона вперто мовчала, тільки пищала, доводячи тональність свого болю до максимальної гучності. Тоді я вирішила послухати душу в тиші. Для цього мені спало на думку використати мову тиші і вібрації тибетської чаші, яка має свою мову звуків. Також мене надихнув метод відомого американського психолога Ріка Хенсона та його “Ди-По-За” (Дихання-Посмішка-Стоп).

Метод, який я використовувала, – це пряме звернення до душі, коли дитину спочатку просять зосередитися на собі і своїй енергії за допомогою тибетської чаші-дзвіночка. Для початку по чаші гонгу м’яко вдаряють. Делікатний звук резонує із замкненою душею. Потім я прошу дітей зробити глибокий вдих, щоб ще більше наблизитися до душі. Коли дитина глибоко видихає, простір в тілі (легені, серце, внутрішня порожнина) звільняється, де душа може знову зайняти своє початкове положення. Колись до війни, до шоку, вона була тут, займала своє законне положення, дихала вільними грудьми, посміхалася.

Я прошу дитину посміхнутися всередині себе. Достатньо скласти губи в усмішку. Це допоможе душі згадати, як вона раніше посміхалася. Бажано, щоб дитина затрималася в цьому стані і дала достатньо часу душі, щоб згадати стан посмішки. Цей крок називається “Зупинка” або “Утримання”, останній з трьох кроків Ди-По-За (дихання-посмішка-зупинка). Кінець цієї усміхненої розмови з душею травмованої дитини позначається гонгом чаші, щоб душа не втекла і залишилася в тілі. Таким чином дитина ніби повертається до себе і тоді можна проводити повноцінне заняття.

Важливо, щоб дитина полюбила чашу і її звук. Для цього за деякий час до використання методу я знайомила дітей з чашею. Чаша знаходиться у вільному доступі в класі. Учні могли взяти її в руки, “пограти на ній”, попрактикувати свої здібності маленького медитатора. Я вибрала найменшу версію чаші, щоб вона поміщалася в долоні дитини. Коли чаша поміщається в долоні (так, ніби Бог або природа зробили в долоні заглиблення, щоб тримати чашу), дитина легенько вдаряє вільною рукою по боковій стороні чаші. Металеві вібрації проходять через нервові закінчення руки, досягаючи подряпаної душі на самому краю. Ці вібрації ніби збирають або перепрошивають пошкоджені травмою нейронні зв’язки, зчитуючи їхній оригінальний відбиток зі спільного сервера десь на небесах. Травмований мозок збирає шматочки нейронних синапсів назад. Діти інтуїтивно відчувають терапевтичний ефект чаші, адже часто просять потримати її або “погратися” на ній. Звісно, таку можливість даю кожному.

Не всі мої учні ще щиро посміхаються, але замерзлі віконця їхніх душ поступово відтають. Якщо регулярно практикувати Ди-По-За, посміхатися травмованій душі дитини, можна розморозити вікна її душі, через які краще побачити дитину, а може, і апостола в ній. Одного з дванадцяти, а може, і всіх.

English:

Olha Samborska

Berlin

14.01.2023

In Ukrainian classes for refugee children, according to the rules of the German Senate of Schooling, there should be twelve children (as the twelve apostles). When I took this position as a teacher of a beginner class, I did not quite understand why twelve. Well, twelve is twelve. “More attention to everyone,” I rejoiced to myself.

But my joy was short-lived. Already in the first months of work at the school, local teachers, whose classes had twice as many children, began to look at me sideways. Some of them smiled sweetly at me, but the coolness was felt in the lower chakras. But I held on. I faltered when the school had a critical situation with the staff and one teacher had to leave the school. Of course, there was fermentation in the masses, because no one wanted to be “superfluous”, that is, laid off.

I once passed a group of teachers on the school playground. “And what is your contract?” I unexpectedly received like a chestnut on the head (we were just standing under this tree). I did not quickly orientate myself and answer, although it is inappropriate to answer such questions as well as inappropriate to ask. My answer caused a goose-cackle among the teachers. I asked what was the matter. They explained about the layoffs, and in their opinion, I “with my three students” should be laid off. In fact, I have not three, but twelve students, but there is a difference for those who have twenty-four or even twenty-eight. The teachers hissed and hollered further, explaining their busy workload. I asked to clarify this issue with the director and left the goose flock.

Soon there was a conversation with the director. The situation was clarified. Teachers of Ukrainian classes in German schools have a special status and are not subject to redundancies that apply to the school as such. I shook my wings, straightened them, and went on my free float around the school. On the advice of the director, I began to avoid geese.

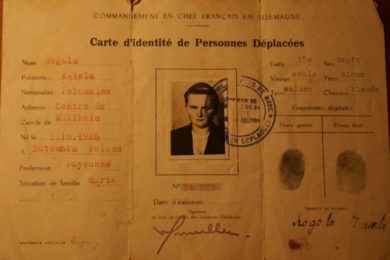

A few more weeks passed. Somehow, after the last week, I understood why there are twelve students in the classes for refugee children, and not twenty-four as in regular classes. When you look at the refugee children, one of whom does not smile at all, the other constantly looks from under his forehead, and you try to pull the soul out of the children to smile and in vain, when you let them out for a break, and after it you can not calm the clots of energy in one wave, when during the lesson you hear out of the blue: “A rocket hit our house and destroyed it,” when the child just heard the word “house” as a trigger. Such “when” surprises are a full lesson and a full day. Gradually, you realise that you are working with children who are really traumatised by the pandemic and war, and in this case this class is equivalent to the class of children with disabilities, who should also be up to twelve, that is, smaller than a regular class, because it is more difficult to work with them. The only difference is that teachers for classes of disabled children are specially trained to work with them. If a disabled child studies in a regular class, a specialist teacher trained to work with disabled children is assigned to him/her and accompanies him/her everywhere.

Of course, Ukrainian refugee children are not disabled in the literal sense of the word, but an individual approach to them would not have been amiss. And the professional qualification of teachers to work with children with traumas would have been useful. And respect for the teacher, who, without special training, has to talk to traumatised children one-on-one, would also not be amiss.

The position of a teacher of the beginner’s class or so called Willkommensclass is new in the German school system. Teachers are usually recruited for it with an emphasis on the qualification of the teacher of German as a foreign language for the integration of the child into the German school. Of course, such German teachers are not always trained trauma therapists. Sometimes one-time and one-hour webinars on how to deal with traumatized children are organized for them. The only thing missing is a systematic methodology for teachers to talk with trauma in children.

Trauma, Ukrainian child trauma, does not speak Ukrainian, as I hoped it would. It speaks to me in the squeaky voice of a child, trapped somewhere between its body and spirit when the war-terrified soul was already on the way to escape from the body, but caught on to the consciousness and hung on to it. It squeaks, sometimes screams, cries, hysterical, as if asking to remove it from the invisible hook of consciousness and pull it out.

For a long time, I tried to pull out the traumatised soul of the child to talk with, but she was stubbornly silent, only squeaking, bringing the tone of her pain to the maximum volume. Then I decided to listen to the soul in silence. To do this, it occurred to me to use the language of silence and vibration of the Tibetan bowl, which has its own language of sound. I was also inspired by the method of the famous American psychologist, Rick Hanson, and his Di-Po-Za (Breath-Smile-Stop).

The method I used is a direct appeal to the soul, when the child is first asked to focus on himself and his energy with the help of a Tibetan bowl-bell. To begin with, the gong bowl is struck gently. The delicate sound resonates with the trapped soul. Then I ask children to take a deep breath to get even closer to the soul. When the child exhales deeply, the space in the body (lungs, heart, inner cavity) is freed up, where the soul can take its original position again. Once before the war, before the shock, it was here, taking its rightful position, breathing on a free chest, smiling.

I ask the child to smile inside himself. It is enough to fold the lips into a smile. This will help the soul to remember how it used to smile. It is desirable that the child stay in this state and give enough time to the soul to remember the smiling state. This step is called Stop or Holding, the last of the three steps of Di-Po-Za (breathing-smiling-stop). The end of this smiling conversation with the soul of the traumatised child is marked by the gong of the bowl so that the soul does not escape and remains in the body. In this way, the child seems to return to himself and then you can conduct a full lesson.

It is important that the child loves the bowl and its sound. For this purpose, for some time before using the method, I introduced the children to the bowl. The bowl is freely available in the classroom. Pupils could take it in their hands, “play on it,” and practice their abilities as a small meditator. I chose the smallest version of the bowl so that it fits in the palm of a child’s hand. When the bowl fits in the palm of the hand (as if God or nature made a hollow in the palm of the hand to hold the bowl), the child gently strikes the side of the bowl with his free hand. Metal vibrations pass through the nerve endings of the hand, reaching the scratched soul on the very edge. These vibrations seem to collect or rewire the neural connections damaged by trauma, reading their original print from a common server somewhere in the heavens. The traumatized brain puts the pieces of neural synapses back together. Children intuitively feel the therapeutic effect of the bowl, because they often ask to hold it or “play” on it. Of course, everyone is given such an opportunity.

Not all my students smile sincerely yet, but the frozen windows of their souls are gradually thawing. If you regularly practice Di-Po-Za, smile at the traumatized child’s soul, you can thaw the windows of their souls, through which you can better see the child, and maybe the apostle in it. One of the twelve, or perhaps all of them.