English version below.

English version below.

Автор: Ольга Самборська

Берлін, 30.01.2023

– Хочеш чаю? – запропонувала вона.

Питання сторіччя! Я могла чекати будь-яку іншу пропозицію від німкені на порозі її квартири, тільки не це. Запросити на чай людину, яка прийшла просто забрати одну річ згідно об’яи в інтернеті, не є ознакою німецької міської культури і навіть жодної її субкультури. Тут на чай не запрошують навіть друзів, не те, щоб людей з вулиці, які просто забігли щось забрати.

Відверто мене це питання загналов ступор. Відмовитися чи погодитися? Що відповісти? Звісно відмовитися згідно правилам доброго тону. Та ні, погодитися, таке пропонують раз в сторіччя, якщо не тисячоліття.

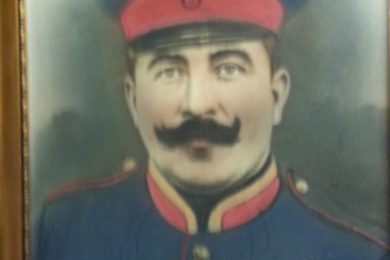

Вона, Евелін, була жінкою старшого віку,коротка стрижка, бадьора в силу свого характеру, привітна. Трохи скошені мигдалеві очі і степовий ніс нагадали мені етнографічні описи з німецької історії про аварів, які колись прийшли на цю землю звідкись зі сходу. Не вистачало лише скіфського ковпачка на голову, щоб вже бачти перед собою історичного пращура берлінців. Вони ж, тодішні степовики, до речі теж привезли з собою культуру пиття чаю в Німеччину.

Евелін відповіла мені на прохання спонсорувати нашому класу українських школярів йога-килимки. Цю об’яву я розмістила на місцевому інтернет-порталі для сусідів, тобто мешканців мого мікрорайону. Знаючи, що багато мешканців Берліна в запалі зайнятися йогою купують для цього йога-килимки, але на першому-другому занятті розуміють, що то не їх польоту заняття і закидають справу, вирішила звернутися до таких. Зустрічала багато подібних об’яв, в яких просто роздаровують іншим йога-килимки, щоб ті не запилювалися. Добра справа заради збереження довкілля проти перевиробництва і перебільшеного споживння. Тому і звернулася з відповідним запитомдо сусідів подарувати безхозні килимки для малих українців, які на них проводять свою йога-терапію.

Це вже друге моє звернення. Перший потік килимків був подарований нашому класу ще восени. Тоді нас було шестеро. Зараз клас вдвічі збільшився і потреба постала знову. Діти мало не б’ються за місце на такому гумовому килимі, коли в нас чергова йога-подорож або медитація. На цих килимках ми і малюємо, і просто відпочиваємо, і граємось. Цілоденне сидіння за партою виснажує дітей. Горизонтальна альтернатива полюбилася дітям. У нас навіть так розставлені парти в класі, щоб посередині класу можна було в будь-який момент розкинути йога-килимки і розслабити замучене довгим сидінням тіло.

Розслаблення потрібне нам, коли в школі час від часу відбувалися збої з внутрішнім гучномовцем-передавачем важливої внутнішньої інформації. Саме ним повідомляють про нагальні шкільні справи або про можливу пожежу. Мої чутливі до сирен українці дуже бояться цього гучномовця, бо по-перше не розуміють, про що він говорить і чи те, що він каже, є загрозливим. Діти мають за собою не найкращий досвід з сиренами в Україні, які повідомлять не про тренувальну, але справжню війну. В Берліні ж, в українському класі, їм довелося зіштовхнутися з тренувальними сиренами, але не менш загрозливими для їх чутливої душі.

Проблема в тому, що кілька разів включалася пожежна сирена, яка повідомляє про виникнення пожежі в школі, мала би бути одноразовою, але чомусь не виключалася, хоча була тренувальною. Короткий вступ«уууу-уууу-ууууу» з подальшим голосом диктора «Ахтурнґ, фойер алам! Бефрайт ір бітте гебойде» повторювався як заїла платівка на протязі години. Діти в чому були повинні були залишити класну кімнату і вибігти на шкільне подвір’я. Звісно, що для моїх українців це було ще тим випробуванням. Цей пожежний аларм виявився зломаним. Чи то батарейки сіли, чи ще якийсь баґ, але сирена не виключалась понад годину. Керівництву школи довелося чекати приїзду фірми, яка виробляє ці аларми, щоб заспопоїти їх верескливе «дитя». Типово німецький технічний ідіотизм!

Який стрес ми пережили, знають мабуть лише наші йога-килимки, на які ми відразу лягаємо, коли весь шкільний сиренний жах закінчується, і медитуємо, робимо різні йога-положення, щоб заспокоїти страх і поговорити з тілом.

….

На вході берлінської квартири до стіни був припертий новенький йога-килимок. Він був запакований в прозору плівку. Невикористаний. Мене це приємно здивувало. З радощів пропоную Евелін шоколадку, яку за неписаними правилами дають тому, хто щось дарує.

«Так будеш чай?»- ще раз перепитує дарувальниця. «Буду!»-ствердно відповідаю і проходжу на невелику кухню відразу біля входу в квартиру. Берлінські квартири старого зразка або як їх ще називають тут«альтбау» вражають своєю глибокою історичністю. На вулиці Гасенгайде, де жила Евелін, вони датуються ще початком минулого століття, коли їх будували для офіцерів пруської армії. В цьому районі, тобто районі Зюдштерну, колись розміщувався цілий гарнізон цісарської армії. Висотні будинки будувалися в такий спосіб, щоб тут могло мешкати як високе керівництво армії, так і рядове, особливо обслуга. Перші могли насолоджуватися світлими квартирами з високими стелями з спеціальною штукатуркою-барельєфами, розписами (зараз вони охороняються державою як пам’ятка культури), а останні жили скромніше, без розмаху, з низькими стелями і в другому ряду квартир, тобто за першим будинком, де і знаходились люксові квартири. Перший ряд квартир німці називають вордерхауc, тобто будинок спереду, і гінтерхаус, тобто задній будинок. Евелін проживали в будинку позаду головного. Ці квартири зазвичай дешевші для зйому, темніші, але тихіші, бо ніби сховані від вуличного шуму. Затишок живе тут вже друге століття.

Я звернула увагу на стару заходжену заcкарузлу підлогу кухні. Дерев»яний «діленбоден» (підлога), який так цінується в Німеччині, був неопрацьований і видається ввібрав в себе весь бруд ще з часів пруського офіцерства. Евелін швидш за все не переймалася станом підлоги. Зате на її столі були свіжі квіти.

Вона поклала переді мною склянку налитого з термосу чаю. Німці дуже люблять термоси і тримають їх поблизу і в праці, і вдома. Мабуть тому пропозиція теплого чаю була добре продуманою.

«А Ви знаєте, що Ви перша людина в Німеччині, яка за час мого двадцятирічного перебування тут запропонувалася мені випити разом чаю!» – починаю нашу розмову. Далі розповідаю, що свого часу в своїй рідній Україні запрошення на чай було природнього традицією, особливо серед сусідів, і як мені цього вистачає.

Евелін вибачливо посміхається. «Так, останнім часом у нас з цим стало важко» – ніби виправдовується вона і вже пояснює, як раніше були часи, коли берлінці (Евелін –корінна берлінка) були привітнішими і навіть ходили один до одного в гості (зараз заведено зустрічатися лише в кафе і ресторанах). «Особливо молоді стали дуже непривітними. Мабуть життя їх дуже стресує»-додає вона.

Далі Евелін розповідає мені до прикладу про її останній досвід ходіння квартирами їхнього будинку, коли вони мали вирішити як будуть користуватися їх газовим опаленням взимку. Високі ціни на газ після початку нападу Росіі на Україну примушують німців шукати альтернативи споживання енергоносііїв. Евелін не може похвалитись привітністю мешканців будинку під час її обходу квартир. Чай їй ніхто не пропонував.

Мене цікавить до якого ж спільного знаменника про газ прийшли мешканці альтбау в Берліні? Запитую Евелін про це. «Сподівалися зробити приєднання до теплової траси, що було б дешевше, але для цього потрібно провести риття траси до нашого будинку, розривати дорогу,» – пояснює вона безвихідне положення газозалежних мешканців будинку і продовжує: «Шольц вже поїхав в Аргентину домовлятися про енергоносії. Це не вихід…» – бідкається, але поки небачить жодної альтернативи.

Наразі тепло зберігає в термосі і в своєму серці.

«Дай Бог, жахіття в Україні швидко закінчиться і питання енергоносіїв вирішиться!» – хочу ніби заспокоїти Евелін, але помічаю, що говорю це більше для себе. Я вже звикла останнім часом заспокоювати себе і всіх поруч, особливо своїх українських учнів, що війна скоро-скоро закінчиться і все у всіх буде добре. На це ми медитуємо на наших йога-килимочках.

Я подякували своїй співрозмовниці за чай, за йога-килимок і з надією в неймовірне залишила її квартиру в гінтер-хаус, пройшла затишним двориком, який розділяє задній будинок від переднього і за хвилю опинилася в шумовитті мого Зюдштерну. На душі було тепло. Не знаю чи від чаю, який зігрів мій шлунок, чи від розмови, яка зігріла душу. А можливо це було співчуття один до одного, яке виникає в розмові двох? Співчуття Евелін до українських дітей і моє співчуття до неї, про яке я б не написала, якби Евелін сама про це не повідомила: у неї не має дітей. Які б не були мотиви: втеча від самотності чи просто гостинність, але якщо такі речі як випадкове запрошення незнайомій людині ще можливе, вияв співчуття один до одного ще можливі, значить ще не все втрачено в цьому скупому на емоції, гостинність і добро світі.

Хто хоче чаю?

Заходьте!

English Version:

Author: Olha Samborska

Berlin, 30.01.2023

Story

“Would you like some tea?” she offered.

The question of the century! I could have expected any other offer from a German woman on the doorstep of her apartment, but not this. Inviting a person to tea who has come just to pick up one thing according to an online ad is not a sign of German urban culture, or even of any of its subcultures. Here, even friends are not invited to tea, let alone people from the street who just came to pick something up.

Frankly, I was stumped by this question. Should I refuse or agree? What should I say? Of course, to refuse according to the rules of good manners. But no, I should accept, as this is offered once in a century, if not a millennium.

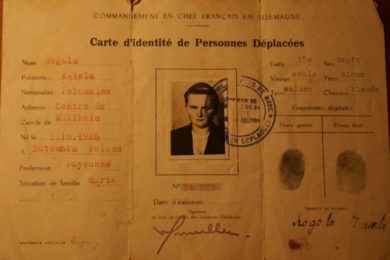

She, Evelyn, was an older woman, with a short haircut, cheerful by nature, and friendly. Her slightly slanted almond eyes and steppe nose reminded me of ethnographic descriptions from German history about the Avar who once came to this land from somewhere in the east. All I needed was a Scythian head cap to see the historical ancestor of the Berliners in front of me. By the way, they, the steppe people of that time, also brought the culture of drinking tea to Germany.

Evelyn responded to my request to sponsor our class of Ukrainian schoolchildren with yoga mats. I posted this announcement on a local Internet portal for neighbours, i.e. residents of my neighbourhood. Knowing that many Berliners buy yoga mats in the heat of the moment, but realise after the first or second class that it’s not their cup of tea and give up, I decided to turn to this kind of service. I have seen many similar ads in which people simply give away yoga mats to others so that they do not get dusty. It’s a very smart exchange to save the climate, that is, against overproduction through overbuying. That’s why I asked my neighbours to donate their not used mats to young Ukrainians who practice yoga therapy on them.

This is my second request. The first batch of mats was donated to our class back in the autumn. There were six of us then. Now the class has doubled in size and the need has arisen again. Children almost fight for a place on such a rubber carpet when we have another yoga trip or meditation. We draw on these mats, and just relax and play. Sitting at a desk all day exhausts children. The horizontal alternative is a favourite of children. We even arrange the desks in the classroom so that yoga mats can be spread out in the middle of the classroom at any time and relax the body, which is tortured by long sitting.

We need relaxation when the school occasionally malfunctions with the internal loudspeaker transmitting important internal information. It is the loudspeaker that informs about urgent school matters or a possible fire. My siren-sensitive Ukrainians are very afraid of this loudspeaker because, first of all, they do not understand what it says and whether what it says is threatening. Children do not have the best experience with sirens in Ukraine, which announce not a training war, but a real war. In Berlin, in the Ukrainian classroom, but german school, they had to deal with training sirens, but no less threatening to their sensitive souls.

The problem was that the fire siren, which was supposed to be a one-time event, went off several times, but for some reason it did not turn off, even though it was a practice siren. The children had to leave the classroom in their clothes and run out into the schoolyard. Of course, for my Ukrainians, this was a challenge. This fire alarm turned out to be broken. Either the batteries were dead or there was some other bug, but the siren did not go off for more than an hour. The school management had to wait for the arrival of the alarm company to calm their screaming “baby”. Typical German technic idiocy!

Only our yoga mats know how much stress we went through, and we immediately lie down on them when the whole school siren horror is over and meditate, do different yoga positions to calm the fear and talk to the body.

At the entrance of the Berlin apartment, a brand new yoga mat was pinned to the wall. It was wrapped in a transparent film. It was unused. I was pleasantly surprised. I gladly offered Evelyn a chocolate bar, which, according to unwritten rules, is given to the person who gives something.

“Do you want tea?” the gift-giver asks again. “Yes, I will!” I answer affirmatively and go to the small kitchen right at the entrance to the apartment. Berlin’s old-style apartments, or “altbau” as they are also called here, are striking in their deep historicity. On Hasenheide Street, where Evelyn lived, they date back to the early twentieth century, when they were built for Prussian army officers. This neighbourhood, the Südstern district, was once home to an entire garrison of the imperial army. The high-rise buildings were built in such a way that both the high command of the army and the rank and file, especially its servants, could live here. The former could enjoy bright apartments with high ceilings, special plaster bas-reliefs, and paintings (now protected by the state as a cultural monument) in front hause, while the latter lived more modestly, without grandeur, with low ceilings and in the second row of apartments, i.e. behind the front house, where the luxury apartments were located. The Germans call the first row of apartments the vorderhaus, or front house, and the hinterhaus, or back house. Evelyn lived in the house at the back. These apartments are usually cheaper to rent, darker, but quieter, because they seem to be hidden from street noise. The Cozinesses have lived here for the second century.

I noticed the old, worn, scuffed floor of the apartment. The wooden “Dielenboden” (floor), which is so valued in Germany, was untreated and seemed to have absorbed all the dirt from the days of the Prussian officers. Evelyn most likely did not care about the condition of the floor. But there were fresh flowers on her table.

She put a glass of tea poured from a thermos in front of me. Germans are very fond of thermoses and keep them close at hand both at work and at home. Perhaps that is why the offer of warm tea was well thought out.

“Do you know that you are the first person in Germany who has offered me a cup of tea in my twenty years of living here?” I begin our conversation. I go on to tell her that in my native Ukraine, invitations to tea were a natural tradition, especially among neighbours, and how much I miss it.

Evelyn smiles apologetically. “Yes, it has become difficult for us lately,” she seems to be making excuses and explains how there used to be times when Berliners (Evelyn is a native Berliner) were more friendly and even visited each other (nowadays, it is customary to meet only in cafes and restaurants). “Especially young people have become very unfriendly. Apparently, life is very stressful for them,” she adds.

Evelyn goes on to tell me about her most recent experience walking around the apartments in their building, when they had to decide how they would use their gas heating in the winter. High gas prices since the beginning of Russia’s attack on Ukraine have forced Germans to look for alternatives to sharing energy. Evelyn is not impressed with the friendliness of the residents during her visits to the apartments. No one offered her tea.

I am interested in what common point the residents of the Altbau (old hause) in Berlin have come to? I ask Evelyn about it. “We were hoping to connect to the heating mains, which would be cheaper, but that would require digging a route to our house and tearing up the road,” – she explains the hopeless situation of the gas-dependent residents of the house and continues: “Kanzler Scholz has already gone to Argentina to negotiate energy supplies. This is not an option.” She laments, but does not see any alternative yet. For now, she keeps warm in a thermos and in her heart.

“God willing, the horror in Ukraine will end soon and the issue of energy will be resolved!” – I want to reassure Evelyn, but I notice that I’m saying it more to myself. I have become accustomed to reassuring myself and everyone around me, especially my Ukrainian students, that the war will end soon and everything will be fine. We meditate on this on our yoga mats.

I thanked my interlocutor for the tea, for the yoga mat, and with hope for the unimaginable left her apartment for the hinterhaus, walked through the cozy courtyard that separates the back house from the front, and in a moment found myself in the noise of my Südstern area. My soul was warm. Whether it was the tea that warmed my stomach or the conversation that warmed my soul. Or perhaps it was the compassion for each other that arises in a conversation between two people? Evelyn’s compassion for Ukrainian children and my compassion for her, which I would not have written about if Evelyn had not told me about it: she has no own children. Whatever the motives: an escape from loneliness or just hospitality, if such things as a casual invitation to a stranger are still possible, if showing compassion for each other is still happening, then all is not lost in this world that is stingy with emotions, hospitality and kindness.

Who wants tea?

Come on in!